INTERVIEW MAGAZINE

Karen Brailsford interviews Spike Lee

November 1992

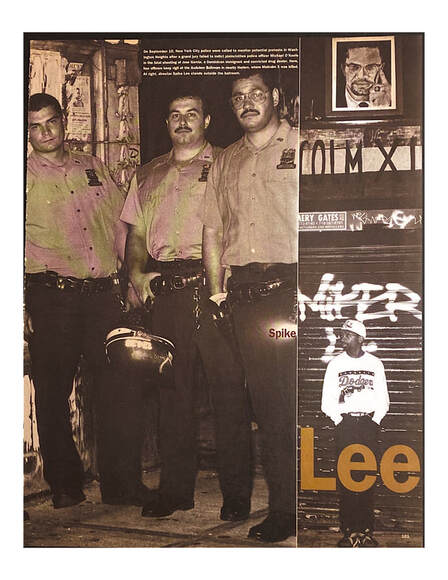

That's my mug on the contributors' page, featured with Elvis Costello, John Leguizamo, Dennis Hopper and Donna Tartt. I talked to Spike Lee about his then upcoming film, Malcolm X. A silly moment: Spike teased me about my key chain, a statuette I'd bought as a souvenir in Africa. "That's a fertility symbol. You'd better be careful!" he warned. "That stuff works."

What Our Contributors Are Up To — A Sampling

KAREN BRAILSFORD

Spike Lee, page 100

While interviewing Spike Lee for this issue, Karen Brailsford, an associate editor at Elle, was struck by the doctor's methodicalness. "Occasionally, he would warm up and joke," she says, "but he would just as quickly cut back to the interview, like, This is business. He's very focused." Her writing has also appeared in The New York Times Book Review, Emerge, and Newsweek.

KAREN BRAILSFORD

Spike Lee, page 100

While interviewing Spike Lee for this issue, Karen Brailsford, an associate editor at Elle, was struck by the doctor's methodicalness. "Occasionally, he would warm up and joke," she says, "but he would just as quickly cut back to the interview, like, This is business. He's very focused." Her writing has also appeared in The New York Times Book Review, Emerge, and Newsweek.

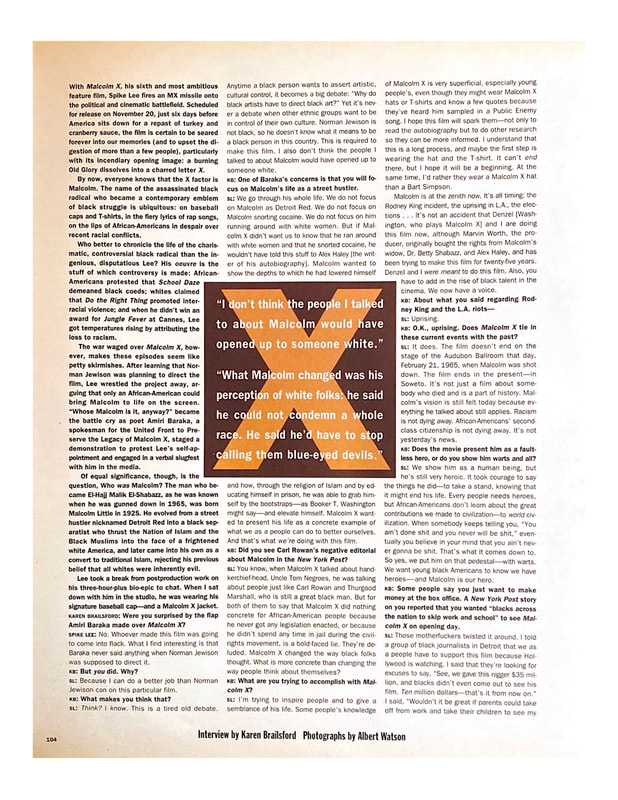

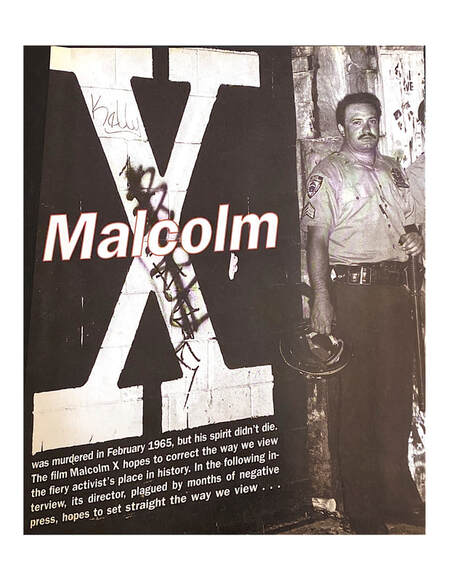

With Malcolm X, his sixth and most ambitious feature film, Spike Lee fires an MX missile onto the political and cinematic battlefield. Scheduled for release on November 20, just six days before America sits down for a repast of Turkey and cranberry sauce, the film is certain to be seared forever into our memories (and to upset the digestion of more than a few people), particularly with its incendiary opening image: a burning Old Glory dissolves into a charred letter X.

By now, everyone knows that the X factor is Malcolm. The name of the assassinated black radical radical who became a contemporary emblem of black struggle is ubiquitous: on baseball caps and T-shirts, in the fiery lyrics of rap songs, on the lips of African-Americans in despair over recent racial conflicts.

Who better to chronicle the life of the charismatic, controversial black radical than the ingenious, disputatious Lee? His oeuvre is the stuff of which controversy is made: African-Americans protested that School Daze demeaned black coeds; whites claimed that Do the Right Thing promoted interracial violence; and when he didn't win an award for Jungle Fever at Cannes, Lee got temperatures rising by attributing the loss to racism.

The war waged over Malcolm X, however, making these episodes seem like petty skirmishes. After learning that Norman Jewison was planning to direct the film, Lee wrestled the project away, arguing that only an African-American could bring Malcolm to life on screen. "Whose Malcolm is it anyway?" became the battle cry as poet Amiri Baraka, a spokesman for the United Front to Preserve the Legacy of Malcolm X, staged a demonstration to protest Lee's self-appointment and engaged in a verbal slugfest with him in the media.

Of equal significance, though, is the question, Who was Malcolm? The man who became El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz, as he was known when he was gunned down in 1965, was born Malcolm Little in 1925. He evolved from a street hustler who thrust the Nation of Islam and the Black Muslims into the face of a frightened white America, and later came into his own as a convert to traditional Islam, rejecting his previous belief that all whites were inherently evil.

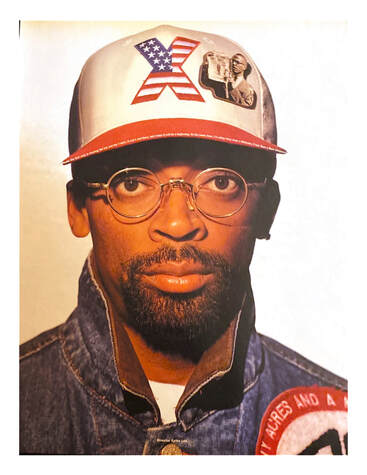

Lee took a break from postproduction work on his three-hour-plus bio-epic to chat. When I sat down with him in the studio, he was wearing his signature baseball cap—and a Malcolm X jacket.

KAREN BRAILSFORD: Were you surprised by the flap Amiri Baraka made over Malcolm X?

SPIKE LEE: No. Whoever made this film was going to come into flack. What I find interesting is that Baraka never said anything when Norman Jewison was supposed to direct it.

KB: But you did. Why?

SL: Because I can do a better job than Norman Jewison can on this particular film.

KB: What makes you think that?

SL: Think? I know. This is a tired old debate. Anytime a black person wants to assert artistic control, cultural control, it becomes a big debate: "Why do black artists have to direct black art?" Yet it's never a debate when other ethnic groups want to be in control of their own culture. Norman Jewison is not black, so he doesn't know what it means to be a black person in this country. This is required to make this film. I also don't think the people I talked to about Malcolm would have opened up to someone white.

KB: One of Baraka's concerns is that you will focus on Malcolm's life as a street hustler.

SL: We go through his whole life. We do not focus on Malcolm as Detroit Red. We do not focus on Malcolm snorting cocaine. We do not focus on him running around with white women. But if Malcom X didn't want us to know that he ran around with white woman and that he snorted cocaine, he wouldn't have told this stuff to Alex Haley [the writer of his autobiography]. Malcolm wanted to show the depth to which he has lowered himself and how, through the religion of Islam and by educating himself in prison, he was able to grab himself by the bootstraps—as Booker T. Washington might say—and elevate himself. Malcolm X wanted to present his life as a concrete example of what we as a people can do to better ourselves. And that's what we're doing with this film.

KB: Did you see Carl Rowan's negative editorial about Malcolm in the New York Post?

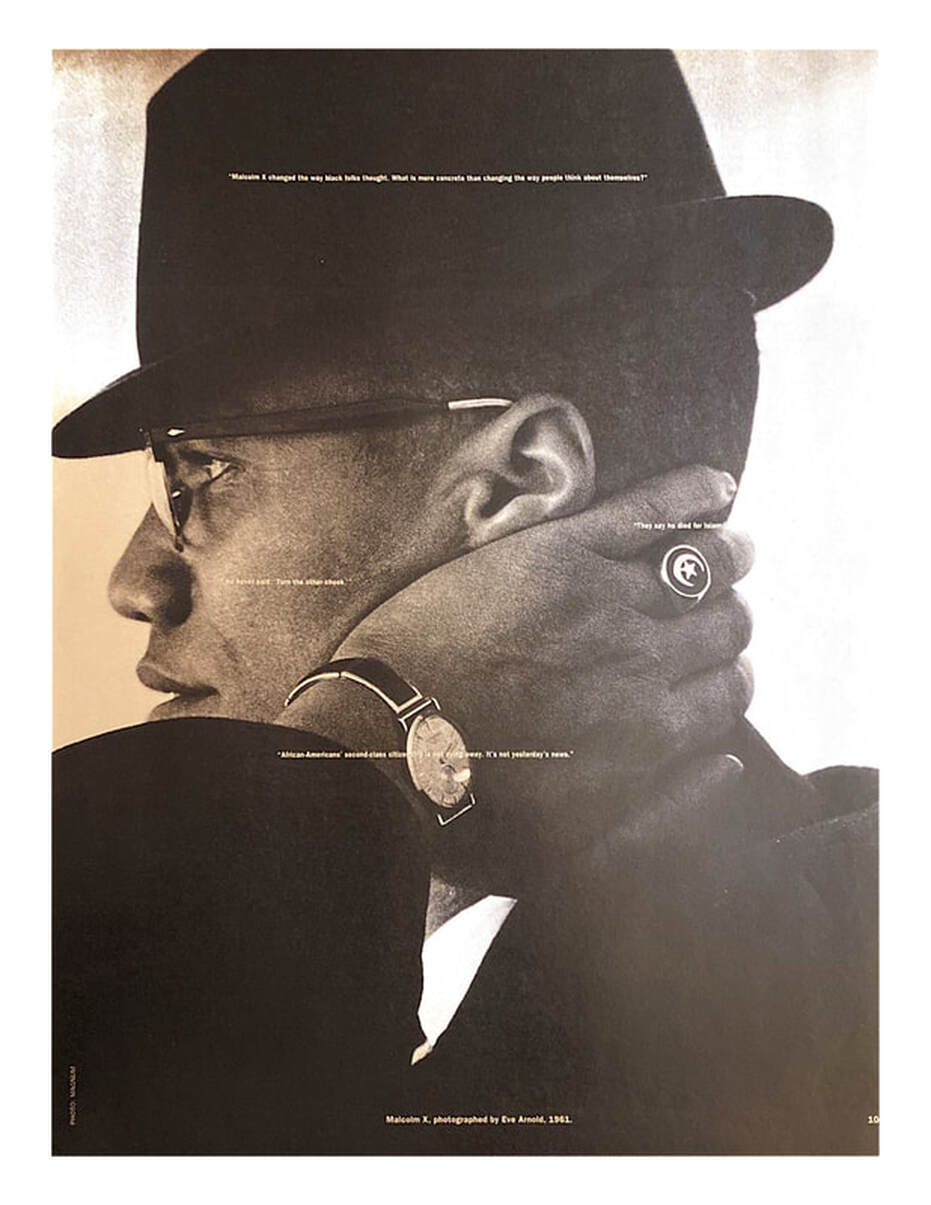

SL: You know, when Malcom X talked about handkerchief-head, Uncle Tom Negroes, he was talking about people like Carl Rowan and Thurgood Marshall, who is still a great black man. But for both of them to say that Malcolm X did nothing concrete for African-American people because he never got any legislation enacted, or because he didn't spend any time in jail during the civil rights movement, is a bold-faced lie. They're deluded. Malcolm X changed the way black folks thought. What is more concrete than changing the way people thing about themselves?

KB: What are you trying to accomplish with Malcolm X?

SL: I'm trying to inspire people and to give a semblance of his life. Some people's knowledge of Malcolm X is very superficial, especially young people's, even though they might wear Malcolm X hats or T-shirts and know a few quotes because they've heard him sampled in a Public Enemy song. I hope this film will spark them—not only to read the autobiography but to do other research so they can be more informed. I understand that this is a long process, and maybe the first step is wearing the hat and the T-shirt. It can end there, but I hope it will be a beginning. At the same time, I'd rather they wear a Malcolm X hat than a Bart Simpson.

Malcolm is at the zenith now. It's all timing: the Rodney King incident, the uprising in L.A., the elections...it's not an accident that Denzel [Washington, who plays Malcolm X] and I are doing this film now, although Marvin Worth, the producer, originally bought the rights from Malcolm's widow, Dr. Betty Shabazz, and Alex Haley, and has been trying to make this film for twenty-five years. Denzel and I were meant to do this film. Also, you have to add in the rise of black talent in the cinema. We now have a voice.

KB: About what you said regarding Rodney King and the L.A. riots--

SL: Uprising.

KB: O.K., uprising. Does Malcolm X tie in these current events with the past?

SL: It does. The film doesn't end on the stage of the Audubon Ballroom that day, February 21, 1965, when Malcolm was shot down. The film ends in the present—in Soweto. It's not just a film about somebody who died and is a part of history. Malcolm's vision is still felt today because everything he talked about still applies. Racism is not dying away. African-Americans' second-class citizenship is not dying away. It's not yesterday's news.

KB: Does the movie present him as a faultless hero, or do you show him warts and all?

SL: We show him as a human being, but he's still very heroic. It took courage to say the things he did—to take a stand, knowing that it might end his life. Every people needs heroes, but African-Amerians don't learn about the great contributions we made to civilization—to world civilization. When somebody keeps telling you, "You ain't done shit and you never will be shit," eventually you believe in your mind that you ain't never gonna be shit. That's what it comes down to. So yes, we put him on a pedestal—with warts. We want young black Americans to know that we have heroes—and Malcolm is our hero.

KB: Some people say you just want to make money at the box office. A New York Post story on your reported that you wanted "blacks across the nation to skip work and school" to see Malcolm X on opening day.

SL: Those motherfuckers twisted it around. I told a group of black journalists in Detroit that we as a people have to support this film because Hollywood is watching. I said that they're looking for excuses to say, "See, we gave this nigger $35 million, and blacks don't even come out to see his film. Ten million dollars—that's it from now on." I said "Wouldn't it be great if parents could take off from work and take their children to see my film?" I directed Malcolm X, but it's a celebration for us. I had to see the motherfuckin' Gone with the Wind when I was in the fourth grade and write a paper about that racist piece of shit! But this got twisted to, "Spike Lee is telling young black kids to play hooky and to drop out of school." Bullshit.

KB: I listened to a recording of one of Malcolm's speeches the other night. He was funny. Many just think of him as a hater of whites, though, and as a violent man. I'm sure few wearing the caps and the T-shirts realize that, at the end of his life, Malcolm made a pilgrimage to Mecca and changed his viewpoint.

SL: But not about everything. Malcolm never changed his views on self-defense. He never said, "Turn the other cheek." What he changed was his perception of white folks: he said he could not condemn a whole race. He said he'd have to stop calling them blue-eyed white devils.

KB: Where did you shoot Malcolm X?

SL: Egypt and South Africa. We also sent an Islamic crew to Mecca. The Saudi government allowed us to shoot hajj two years in a row.

KB: Why were you given permission?

SL: Malcolm X is considered a martyr. They say he died for Islam. We were the first [crew] ever allowed to bring a movie camera into the holy city.

KB: When did you first think you wanted to make this movie?

SL: After Do the Right Thing. But there are images of Malcolm X in She's Gotta Have It and School Daze.

KB: Wasn't Nola Darling [She’s Gotta Have It’s lead character] born on Malcolm's birthday?

SL: Something like that. [laughs heartily] So it's been there in the subconscious. It was ordained.

KB: This is an awful segue, but speaking of Nola Darling...you've received considerable criticism about your depiction of women.

SL: Not considerable. Let's not use that word.

KB: O.K. Let's just say you've received criticism. What do you have to say about this? You're yawning.

SL: The yawn has nothing to do with the question. I wouldn't say it's criticism. There are feminists who swear by She's Gotta Have It. Then again, I've met feminists who hate it. As for School Daze, I think women were mad because the female characters weren't given the same I intellect as the men. But I was dealing with the people I went to school with and the women who lived and died for their men and their fraternities. This is not to say that's the only type of black woman in America. But this problem always arises when there are few black films out. I think She's Gotta Have It may have been the only black film that year, so, unfortunately, Nola Darling had to represent every single black woman. And that's a very unfair burden.

KB: Isn't that the same burden that you've had to bear as a filmmaker?

SL: But not any longer. It's not like it used to be. I will say that we could have given more. School Daze was more about the men. I acknowledge it’s a weakness on my part. Every filmmaker has a weakness, and that has been one of mine. I've been trying to work on it: the way we deal with women in Malcolm X--especially Betty Shabazz...well, you won't hear those rumblings about this film.

KB: You said your depiction of women is one of your weaknesses. What are your others?

SL: I knew you'd pick that up. [smiles]

KB: Well, to turn it around, then, what in your next film will you strive to--

SL: I don't know what my next film is going to be. That's the only weakness I'll acknowledge. I have heard another criticism—that there's too much going on in my films. But that's the way I make films.

KB: The controversies surrounding your films and the issues you raise tend to overshadow the technique.

SL: That's true. Few write about Ernest Dickerson's great cinematography. It's a shame when the polemics or the fireworks of a film obscure your craft. Our films are technically crafted as well as anybody's. We take great pride in this art called cinema. We're not bullshittin' you.

KB: What would you say gets left out of articles about you?

SL: Truth! [laughs] People don't read the story, but they read the headlines and come away with that imprinted on their brain: I'm a racist, I'm an angry black man, I hate white people.

KB: October Esquire's cover story on you was titled "Spike Lee Hates Your Cracker Ass."

SL: I'm going to go to my grave with this big sign on my neck that says SPIKE LEE IS A RACIST AND HATES WHITE PEOPLE. When you read that, it seems that I said that, that it's a quote.

KB: That title is about as inflammatory as the media predictions that Do the Right Thing would start race riots. Are you concerned that this type of publicity might affect Malcolm X?

SL: A lot of white moviegoers were scared to see Do the Right Thing because they read that it was going to cause riots. I know that same type of bullshit is going to start popping up again. I just hope people are now too intelligent to fall for that okeydoke boody-poop bullshit twice. We do not want white moviegoers to fear seeing this film! Do not believe those articles about there being an angry black man ready to fuck you up! The media just plays on white hysteria. Every day white people say to me, "Do the Right Thing was one of my favorite movies." And I always ask them, "Did you see the film in the theater?" Seventy-five percent say they saw it on tape—in the safety and comfort of their home—because they were tricked into thinking that if they saw the film in the theaters, they would end up in the middle of an angry black mob. So, go see the film in the theater. And you don't have to take off November 20! [laughs]

KB: You said you don't know what your next film is going to be. Are you going to take a break?

SL: Have to.

KB: It's been, what? Six films in--

SL: Seven years. Back to back to back to back to back to back. I want to get married one day, Allah willing. Yeah, there's a good sister out there. Operator's standing by now.

KB: I wouldn't think it's so hard to meet women. Or are you so focused on your films that--

SL: That what? I can't meet women?

KB: Well, no, it's easy to meet women. But it's another thing to cultivate a relationship, to grow together.

SL: I guess I just have to do some more raking. [laughs] And I'm not going to use the word "ho', " either!

KB: Good. How do you feel about interracial relationships?

SL: I've said on record that if interracial relationships are based on sexual mythology and that kind of stuff, then they're going to crumble. That's why it did not work between Flipper and Angie [in Jungle Fever]. But look at the relationship that will develop between Paulie and Tyra Ferrell’s character. They are going to weather the storm because it’s built on something concrete—on genuine feelings toward each other. Jungle Fever showed my thoughts on interracial relationships in America. The film does not state that all interracial relationships are fake and book us and will not work. I never said that. I will never say that. But they are still a whole lot of black men with white women, and though it’s 1992, for some it comes down to having that prize on your arm.

KB: Have you ever dated white women?

SL: Never.

KB: Would you ever?

SL: I doubt it. I’m just not attracted to them. I’m not going to lie—I’m not going to lie. To me black women are too beautiful. There’s just no need to go elsewhere. Some men don’t like fat women, some men don’t like skinny women. I’m just not attracted in that way and that’s been twisted to, “He’s a racist. He’s prejudiced against whites.” That’s not the case. I’m just not going to marry a white woman. Plain and simple.

KB: How does Malcolm X compare to your previous work?

SL: This is my best film.

KB: Why? Technically? Because of it’s message?

SL: Everything.

KB: Everything?

SL: Everything. [nods, smiling] This the most important one.

By now, everyone knows that the X factor is Malcolm. The name of the assassinated black radical radical who became a contemporary emblem of black struggle is ubiquitous: on baseball caps and T-shirts, in the fiery lyrics of rap songs, on the lips of African-Americans in despair over recent racial conflicts.

Who better to chronicle the life of the charismatic, controversial black radical than the ingenious, disputatious Lee? His oeuvre is the stuff of which controversy is made: African-Americans protested that School Daze demeaned black coeds; whites claimed that Do the Right Thing promoted interracial violence; and when he didn't win an award for Jungle Fever at Cannes, Lee got temperatures rising by attributing the loss to racism.

The war waged over Malcolm X, however, making these episodes seem like petty skirmishes. After learning that Norman Jewison was planning to direct the film, Lee wrestled the project away, arguing that only an African-American could bring Malcolm to life on screen. "Whose Malcolm is it anyway?" became the battle cry as poet Amiri Baraka, a spokesman for the United Front to Preserve the Legacy of Malcolm X, staged a demonstration to protest Lee's self-appointment and engaged in a verbal slugfest with him in the media.

Of equal significance, though, is the question, Who was Malcolm? The man who became El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz, as he was known when he was gunned down in 1965, was born Malcolm Little in 1925. He evolved from a street hustler who thrust the Nation of Islam and the Black Muslims into the face of a frightened white America, and later came into his own as a convert to traditional Islam, rejecting his previous belief that all whites were inherently evil.

Lee took a break from postproduction work on his three-hour-plus bio-epic to chat. When I sat down with him in the studio, he was wearing his signature baseball cap—and a Malcolm X jacket.

KAREN BRAILSFORD: Were you surprised by the flap Amiri Baraka made over Malcolm X?

SPIKE LEE: No. Whoever made this film was going to come into flack. What I find interesting is that Baraka never said anything when Norman Jewison was supposed to direct it.

KB: But you did. Why?

SL: Because I can do a better job than Norman Jewison can on this particular film.

KB: What makes you think that?

SL: Think? I know. This is a tired old debate. Anytime a black person wants to assert artistic control, cultural control, it becomes a big debate: "Why do black artists have to direct black art?" Yet it's never a debate when other ethnic groups want to be in control of their own culture. Norman Jewison is not black, so he doesn't know what it means to be a black person in this country. This is required to make this film. I also don't think the people I talked to about Malcolm would have opened up to someone white.

KB: One of Baraka's concerns is that you will focus on Malcolm's life as a street hustler.

SL: We go through his whole life. We do not focus on Malcolm as Detroit Red. We do not focus on Malcolm snorting cocaine. We do not focus on him running around with white women. But if Malcom X didn't want us to know that he ran around with white woman and that he snorted cocaine, he wouldn't have told this stuff to Alex Haley [the writer of his autobiography]. Malcolm wanted to show the depth to which he has lowered himself and how, through the religion of Islam and by educating himself in prison, he was able to grab himself by the bootstraps—as Booker T. Washington might say—and elevate himself. Malcolm X wanted to present his life as a concrete example of what we as a people can do to better ourselves. And that's what we're doing with this film.

KB: Did you see Carl Rowan's negative editorial about Malcolm in the New York Post?

SL: You know, when Malcom X talked about handkerchief-head, Uncle Tom Negroes, he was talking about people like Carl Rowan and Thurgood Marshall, who is still a great black man. But for both of them to say that Malcolm X did nothing concrete for African-American people because he never got any legislation enacted, or because he didn't spend any time in jail during the civil rights movement, is a bold-faced lie. They're deluded. Malcolm X changed the way black folks thought. What is more concrete than changing the way people thing about themselves?

KB: What are you trying to accomplish with Malcolm X?

SL: I'm trying to inspire people and to give a semblance of his life. Some people's knowledge of Malcolm X is very superficial, especially young people's, even though they might wear Malcolm X hats or T-shirts and know a few quotes because they've heard him sampled in a Public Enemy song. I hope this film will spark them—not only to read the autobiography but to do other research so they can be more informed. I understand that this is a long process, and maybe the first step is wearing the hat and the T-shirt. It can end there, but I hope it will be a beginning. At the same time, I'd rather they wear a Malcolm X hat than a Bart Simpson.

Malcolm is at the zenith now. It's all timing: the Rodney King incident, the uprising in L.A., the elections...it's not an accident that Denzel [Washington, who plays Malcolm X] and I are doing this film now, although Marvin Worth, the producer, originally bought the rights from Malcolm's widow, Dr. Betty Shabazz, and Alex Haley, and has been trying to make this film for twenty-five years. Denzel and I were meant to do this film. Also, you have to add in the rise of black talent in the cinema. We now have a voice.

KB: About what you said regarding Rodney King and the L.A. riots--

SL: Uprising.

KB: O.K., uprising. Does Malcolm X tie in these current events with the past?

SL: It does. The film doesn't end on the stage of the Audubon Ballroom that day, February 21, 1965, when Malcolm was shot down. The film ends in the present—in Soweto. It's not just a film about somebody who died and is a part of history. Malcolm's vision is still felt today because everything he talked about still applies. Racism is not dying away. African-Americans' second-class citizenship is not dying away. It's not yesterday's news.

KB: Does the movie present him as a faultless hero, or do you show him warts and all?

SL: We show him as a human being, but he's still very heroic. It took courage to say the things he did—to take a stand, knowing that it might end his life. Every people needs heroes, but African-Amerians don't learn about the great contributions we made to civilization—to world civilization. When somebody keeps telling you, "You ain't done shit and you never will be shit," eventually you believe in your mind that you ain't never gonna be shit. That's what it comes down to. So yes, we put him on a pedestal—with warts. We want young black Americans to know that we have heroes—and Malcolm is our hero.

KB: Some people say you just want to make money at the box office. A New York Post story on your reported that you wanted "blacks across the nation to skip work and school" to see Malcolm X on opening day.

SL: Those motherfuckers twisted it around. I told a group of black journalists in Detroit that we as a people have to support this film because Hollywood is watching. I said that they're looking for excuses to say, "See, we gave this nigger $35 million, and blacks don't even come out to see his film. Ten million dollars—that's it from now on." I said "Wouldn't it be great if parents could take off from work and take their children to see my film?" I directed Malcolm X, but it's a celebration for us. I had to see the motherfuckin' Gone with the Wind when I was in the fourth grade and write a paper about that racist piece of shit! But this got twisted to, "Spike Lee is telling young black kids to play hooky and to drop out of school." Bullshit.

KB: I listened to a recording of one of Malcolm's speeches the other night. He was funny. Many just think of him as a hater of whites, though, and as a violent man. I'm sure few wearing the caps and the T-shirts realize that, at the end of his life, Malcolm made a pilgrimage to Mecca and changed his viewpoint.

SL: But not about everything. Malcolm never changed his views on self-defense. He never said, "Turn the other cheek." What he changed was his perception of white folks: he said he could not condemn a whole race. He said he'd have to stop calling them blue-eyed white devils.

KB: Where did you shoot Malcolm X?

SL: Egypt and South Africa. We also sent an Islamic crew to Mecca. The Saudi government allowed us to shoot hajj two years in a row.

KB: Why were you given permission?

SL: Malcolm X is considered a martyr. They say he died for Islam. We were the first [crew] ever allowed to bring a movie camera into the holy city.

KB: When did you first think you wanted to make this movie?

SL: After Do the Right Thing. But there are images of Malcolm X in She's Gotta Have It and School Daze.

KB: Wasn't Nola Darling [She’s Gotta Have It’s lead character] born on Malcolm's birthday?

SL: Something like that. [laughs heartily] So it's been there in the subconscious. It was ordained.

KB: This is an awful segue, but speaking of Nola Darling...you've received considerable criticism about your depiction of women.

SL: Not considerable. Let's not use that word.

KB: O.K. Let's just say you've received criticism. What do you have to say about this? You're yawning.

SL: The yawn has nothing to do with the question. I wouldn't say it's criticism. There are feminists who swear by She's Gotta Have It. Then again, I've met feminists who hate it. As for School Daze, I think women were mad because the female characters weren't given the same I intellect as the men. But I was dealing with the people I went to school with and the women who lived and died for their men and their fraternities. This is not to say that's the only type of black woman in America. But this problem always arises when there are few black films out. I think She's Gotta Have It may have been the only black film that year, so, unfortunately, Nola Darling had to represent every single black woman. And that's a very unfair burden.

KB: Isn't that the same burden that you've had to bear as a filmmaker?

SL: But not any longer. It's not like it used to be. I will say that we could have given more. School Daze was more about the men. I acknowledge it’s a weakness on my part. Every filmmaker has a weakness, and that has been one of mine. I've been trying to work on it: the way we deal with women in Malcolm X--especially Betty Shabazz...well, you won't hear those rumblings about this film.

KB: You said your depiction of women is one of your weaknesses. What are your others?

SL: I knew you'd pick that up. [smiles]

KB: Well, to turn it around, then, what in your next film will you strive to--

SL: I don't know what my next film is going to be. That's the only weakness I'll acknowledge. I have heard another criticism—that there's too much going on in my films. But that's the way I make films.

KB: The controversies surrounding your films and the issues you raise tend to overshadow the technique.

SL: That's true. Few write about Ernest Dickerson's great cinematography. It's a shame when the polemics or the fireworks of a film obscure your craft. Our films are technically crafted as well as anybody's. We take great pride in this art called cinema. We're not bullshittin' you.

KB: What would you say gets left out of articles about you?

SL: Truth! [laughs] People don't read the story, but they read the headlines and come away with that imprinted on their brain: I'm a racist, I'm an angry black man, I hate white people.

KB: October Esquire's cover story on you was titled "Spike Lee Hates Your Cracker Ass."

SL: I'm going to go to my grave with this big sign on my neck that says SPIKE LEE IS A RACIST AND HATES WHITE PEOPLE. When you read that, it seems that I said that, that it's a quote.

KB: That title is about as inflammatory as the media predictions that Do the Right Thing would start race riots. Are you concerned that this type of publicity might affect Malcolm X?

SL: A lot of white moviegoers were scared to see Do the Right Thing because they read that it was going to cause riots. I know that same type of bullshit is going to start popping up again. I just hope people are now too intelligent to fall for that okeydoke boody-poop bullshit twice. We do not want white moviegoers to fear seeing this film! Do not believe those articles about there being an angry black man ready to fuck you up! The media just plays on white hysteria. Every day white people say to me, "Do the Right Thing was one of my favorite movies." And I always ask them, "Did you see the film in the theater?" Seventy-five percent say they saw it on tape—in the safety and comfort of their home—because they were tricked into thinking that if they saw the film in the theaters, they would end up in the middle of an angry black mob. So, go see the film in the theater. And you don't have to take off November 20! [laughs]

KB: You said you don't know what your next film is going to be. Are you going to take a break?

SL: Have to.

KB: It's been, what? Six films in--

SL: Seven years. Back to back to back to back to back to back. I want to get married one day, Allah willing. Yeah, there's a good sister out there. Operator's standing by now.

KB: I wouldn't think it's so hard to meet women. Or are you so focused on your films that--

SL: That what? I can't meet women?

KB: Well, no, it's easy to meet women. But it's another thing to cultivate a relationship, to grow together.

SL: I guess I just have to do some more raking. [laughs] And I'm not going to use the word "ho', " either!

KB: Good. How do you feel about interracial relationships?

SL: I've said on record that if interracial relationships are based on sexual mythology and that kind of stuff, then they're going to crumble. That's why it did not work between Flipper and Angie [in Jungle Fever]. But look at the relationship that will develop between Paulie and Tyra Ferrell’s character. They are going to weather the storm because it’s built on something concrete—on genuine feelings toward each other. Jungle Fever showed my thoughts on interracial relationships in America. The film does not state that all interracial relationships are fake and book us and will not work. I never said that. I will never say that. But they are still a whole lot of black men with white women, and though it’s 1992, for some it comes down to having that prize on your arm.

KB: Have you ever dated white women?

SL: Never.

KB: Would you ever?

SL: I doubt it. I’m just not attracted to them. I’m not going to lie—I’m not going to lie. To me black women are too beautiful. There’s just no need to go elsewhere. Some men don’t like fat women, some men don’t like skinny women. I’m just not attracted in that way and that’s been twisted to, “He’s a racist. He’s prejudiced against whites.” That’s not the case. I’m just not going to marry a white woman. Plain and simple.

KB: How does Malcolm X compare to your previous work?

SL: This is my best film.

KB: Why? Technically? Because of it’s message?

SL: Everything.

KB: Everything?

SL: Everything. [nods, smiling] This the most important one.