PEOPLE

Voices From the Fight Againt Racism

Karen Brailsford, Amandla Stenberg's Mom, Echoes MLK in Fight Against Racism: 'We Shall Overcome'

July 31, 2020

Read story online.or below.

Karen Brailsford is a spiritual guide and the mother of actress Amandla Stenberg. From 1994-2003 she worked as a correspondent in PEOPLE's Los Angeles bureau. Her first book, Sacred Landscapes of the Soul: Aligning with the Divine Wherever You Are (Wyatt-MacKenzie), publishes in September. Here, she writes about growing up in the South Bronx in the 1970s and how it prepared her for navigating various cultural, social and political landscapes.

It is either Jan. 15, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s birthday, or perhaps it’s April 4, the anniversary of his last day. I know it must be at the beginning of the 1970s because I can see through the ephemeral film of memory directly into the kitchen area of the small, South Bronx apartment where we lived until I was 8 and which later became known as “the old house.”

We are intent upon honoring Dr. King — his birthday, his death, his life. After burning off some kinetic energy to James Brown’s “Say It Loud, I’m Black and I’m Proud,” my sister, brother and I stand in a circle holding hands and begin to slowly rotate clockwise. Our voices are so pure the notes hover then crystallize in the air for a nanosecond before splintering like icicles upon the linoleum floor.

We shall overcome

We shall overcome

We shall overcome, someday

The word “someday” becomes a chant as we stretch it over six syllables — “someday ay ay ay ay.” This “someday” is way off in the distant future, signaling the chasm between the mountaintop and the Promised Land of which Dr. King spoke. And yet we remain hopeful.

Oh, deep in my heart

I do believe

We shall overcome, someday.

We circle and sing long past the time the Magnavox usually flickered with images of Fred Rogers returning his red sweater to the closet, at which point our father — whom we called “Daydee” (I had rejected the short vowel “a” and my younger siblings followed suit) — would walk through the door after work at the auto parts store.

I have heard this protest song in my head numerous times. It has become my life’s refrain.

One morning when crossing the street to catch the 86th Street crosstown bus after coming up from inside the bowels of the Lexington Avenue subway, a man in his 30s, white and dressed in a suit, approached. I was 14 years old and on my way to Brearley, the private girls’ school I attended from grades six to 12 on a full scholarship after my fifth-grade teacher, Jonathan Kolb, singled me out for the independent schools application process. The daily trip transported me across vastly different geographical, cultural and economic landscapes and was sometimes punctuated with surprises. Once I caught sight of Rep. Bella Abzug crowned in one of her signature hats on this stretch of sidewalk. On another occasion I met TV’s Kojak, the smooth-pated Telly Savalas.

On this particular morning, the white man reached back with one arm as if throwing a discus and then slapped me in the face. Stunned, I looked back to see him continue walking on, as if nothing had happened. Later when I told others, including my mother, about the incident, they could not fathom it. “Perhaps it was an accident,” they said. I knew it was because I was Black.

We shall overcome, someday.

Brearley was recently in the news after the media got wind of the Instagram page @blackatbrearley, where students detailed horrifying racist experiences. The school has responded by launching a comprehensive anti-racist initiative, which heartens me. I had mostly a positive experience, though I do recall the elderly music teacher's observation as I stood next to her at the piano and sang. “You have such darling little African ears," she said.

Years later, while walking to my room at Yale one night, the N-word came crashing through the air. I looked up to see perched on a ledge a white woman I presumed to be a schoolmate. Another time, a white woman whom I met through work and considered a friend patted me on the head and declared, “You are so cute, just like a little monkey.”

We shall overcome, someday.

The anthem’s dirge-like notes echoed in my head once again on election night in 2012. For months I had been convinced that President Barack Obama could not possibly win a second term. It seemed too much to hope for. His first win had seemed to me to be a reckoning of sorts. One night shortly before he was elected in 2008, I had a vision of a dozen whispering slaves stealing away in a forest in the middle of the night. The earth beneath them crimsoned over with blood and then, a clearing.

I had glimpsed these forefathers and foremothers before, while in the woods of North Carolina on the set of The Hunger Games. I interpreted the vision to mean that every single one of the Black bodies that had been harnessed to build this country, and even those who never made it across the Middle Passage, were operating in concert to bring about his presidency. The North Star was beckoning, his destiny was beckoning and it was all divinely ordained.

I celebrated right along with the ancestors at the 2008 Democratic Convention in Denver and during inauguration week in the nation’s capital. I had attended as a member of the Agape International Spiritual Center’s choir, and we sang back up for John Legend, will.i.am. Seal, Faith Hill and Mary J. Blige at various events. For a time the anthem was overtaken by McFadden & Whitehead’s “Ain’t No Stopping Us Now,” which had blared in Denver. Instead of circling somberly in a circle, we danced in Soul Train line ecstasy.

When it was announced in 2012 that Obama had been re-elected I immediately called my sister. “He did it!” we exclaimed practically in unison. And then we both began to gut-sob.

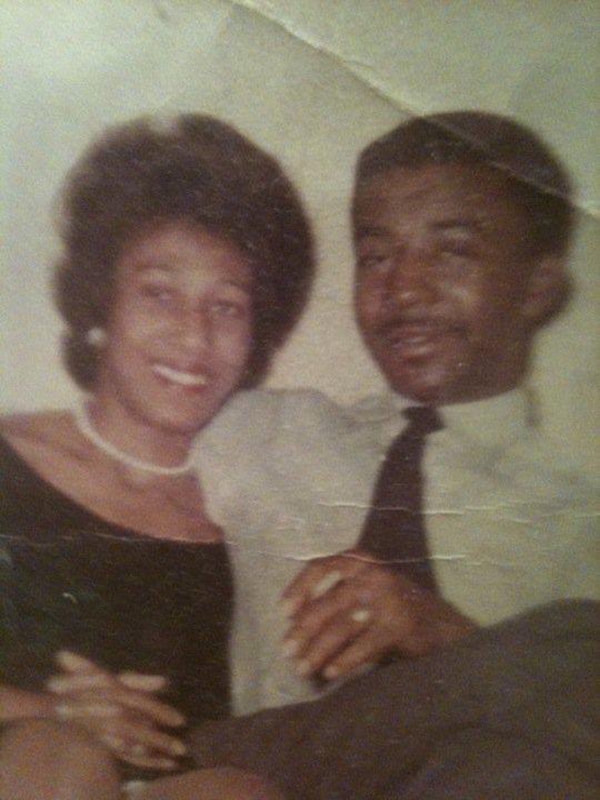

I was thinking of my parents who had died two years apart a decade earlier and wishing they were alive to witness the historic moment. The eldest of 12, Daydee was born and raised in Summerton, South Carolina, the site of the first of five cases that were combined to form Brown v. Board of Education. He had watched his father, my grandfather Willie Friendly Brailsford, Sr., a pipe-smoking farmer and civic activist, ferry neighbors to the polls during elections. Later, Daydee joined the Air Force and two of his brothers served in Vietnam, so it’s no wonder politics and opinions were regular fodder for conversation in our household. I can recall the collective side-eye given my mother’s brother when he announced that he had just voted for Richard Nixon. I remember the Watergate hearings and sitting riveted, glued to the television with my family the night Nixon resigned.

It’s a political legacy that lives on. In 2011 I watched proudly as my daughter, Amandla, stood at the podium alongside Cicely Tyson at the dedication of the Martin Luther King, Jr. memorial in Washington, D.C. In what would become the first of many political statements she would make, she honored the four little girls who were killed in the Birmingham church bombing: Addie Mae Collins. Cynthia Wesley. Carole Robertson. Carol Denise McNair. Yes, say their names!

We shall overcome, someday.

In March 2014, I lined up at Barnes & Noble in Los Angeles for hours to attend President Jimmy Carter’s book signing. His sparkling blue eyes gazed up and through me as he signed a copy of his new book, A Call to Action: Women, Religion, Violence, and Power. “And how are you today?” he asked, unexpectedly. “I’m just fine, Mr. President,” I replied.

The book’s title feels acutely pertinent right now. More recently, the memory of the sidewalk attacker, which had receded somewhat, came roiling into my awareness as I watched Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez deliver her eloquently blistering speech on the House floor. Women, religion, violence and power all play a role.

According to the congresswoman, Rep. Ted Yoho called her a "f---ing b----" for linking poverty to crime rates in New York City. (He has since resigned from the board of a Christian organization.) Eventually, in the 1990s, my family returned to the block of “the old house” after purchasing a newly built home there. Many of the buildings on that street — and in the South Bronx — had famously been burned to the ground in the previous two decades. Politicians and sociologists came to survey the devastation. Even the pope made a pit stop. From my kitchen window, I watched him wave to the crowds as his caravan slow-motored down St. Ann’s Avenue past the church grounds where Founding Father Gouverneur Morris, known for handwriting the American Constitution and delivering unpopular, anti-slavery speeches, is buried. But out of the ashes arose new houses as developers began investing in the area. When I mentioned my family’s habitat trajectory to someone who recently moved to the neighborhood, he smartly observed, “The story of your family seems to have been part and parcel of the times and the city! These stories need to be told by people who lived them instead of by academics who studied them.”

AOC knows the truth, and so do I.

We shall overcome

We shall overcome

We shall overcome, someday

Ay, ay, ay, ay

As I write these concluding lines, my television shows the funeral procession of Rep. John Lewis. Teary-eyed, I listen to the accompanying music, "We Shall Overcome."

We shall overcome

We shall overcome

We shall overcome, someday

Ay, ay, ay, ay

As I write these concluding lines, my television shows the funeral procession of Rep. John Lewis. Teary-eyed, I listen to the accompanying music, "We Shall Overcome."

To help combat systemic racism, consider learning from or donating to these organizations:

• Campaign Zero (joincampaignzero.org) which works to end police brutality in America through research-proven strategies.

• ColorofChange.org works to make government more responsive to racial disparities.

• National Cares Mentoring Movement (caresmentoring.org) provides social and academic support to help Black youth succeed in college and beyond.